Advertisement

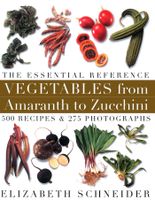

Taro, Dasheen, Eddo

Colocasia esculenta

Appears in

Published 2001

Also

cocoyam orold cocoyam ,coco ,eddoes ,colocasia ,malanga andmalanga isleña (Latin American) ,satoimo (Japanese) ,woo tau (Chinese) ,gabi (Philippine) ,arbi orarvi andpatra (Indian)

Is it possible to summarize briefly the significance of an Old World plant that has been a staff of life in warm, humid regions worldwide? A plant that has probably been cultivated for 10, 000 years— longer than wheat or barley? A food so common that it has hundreds of current names (including some of the American market names selected above)? No, I’m sad to say. Moreover, although the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations lists 44 countries that grew taro in 1999, and the University of Hawaii lists 85 present cultivars, when it comes to mainland North America taro is just another “ethnic vegetable.”